Long before modern rulers and digital scales, ancient civilizations developed sophisticated systems to measure their world, leaving behind clues that continue to intrigue researchers today.

🏛️ The Dawn of Measurement in Human Civilization

The story of measurement begins not with precision instruments, but with the human body itself. Our prehistoric ancestors recognized the need to quantify their environment for survival, trade, and construction. Archaeological evidence suggests that even before written language emerged, early humans were already developing standardized ways to measure distance, weight, and volume.

The transition from nomadic hunter-gatherers to settled agricultural communities around 10,000 BCE created an urgent need for reliable measurement systems. Farmers needed to divide land, measure grain harvests, and track seasonal cycles. These practical requirements became the foundation for some of humanity’s earliest technological innovations.

Interestingly, many prehistoric measurement units were based on readily available references: the length of a forearm, the span of a hand, or the distance covered in a day’s walk. This anthropometric approach to measurement wasn’t arbitrary—it reflected a deep understanding that standardization required references that everyone possessed.

📏 Body-Based Units: The Original Standard

The human body served as the first universal measuring tool, and traces of these ancient standards persist in modern measurement systems. The cubit, derived from the Latin “cubitum” meaning elbow, measured the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger—approximately 18 to 22 inches depending on the individual.

Evidence of the cubit appears across multiple ancient civilizations, from Mesopotamia to Egypt, suggesting either independent development or cultural exchange. The Egyptian royal cubit, standardized around 2700 BCE, measured approximately 20.6 inches and was divided into smaller units called palms and digits, demonstrating remarkable sophistication in fractional measurement.

Other body-based measurements included:

- The foot: literally based on the length of a human foot, typically 11 to 13 inches

- The pace: the distance covered in a single step, roughly 2.5 feet

- The span: the width of an outstretched hand, approximately 9 inches

- The fathom: the distance between outstretched arms, around 6 feet

🗿 Megalithic Mysteries and the Megalithic Yard

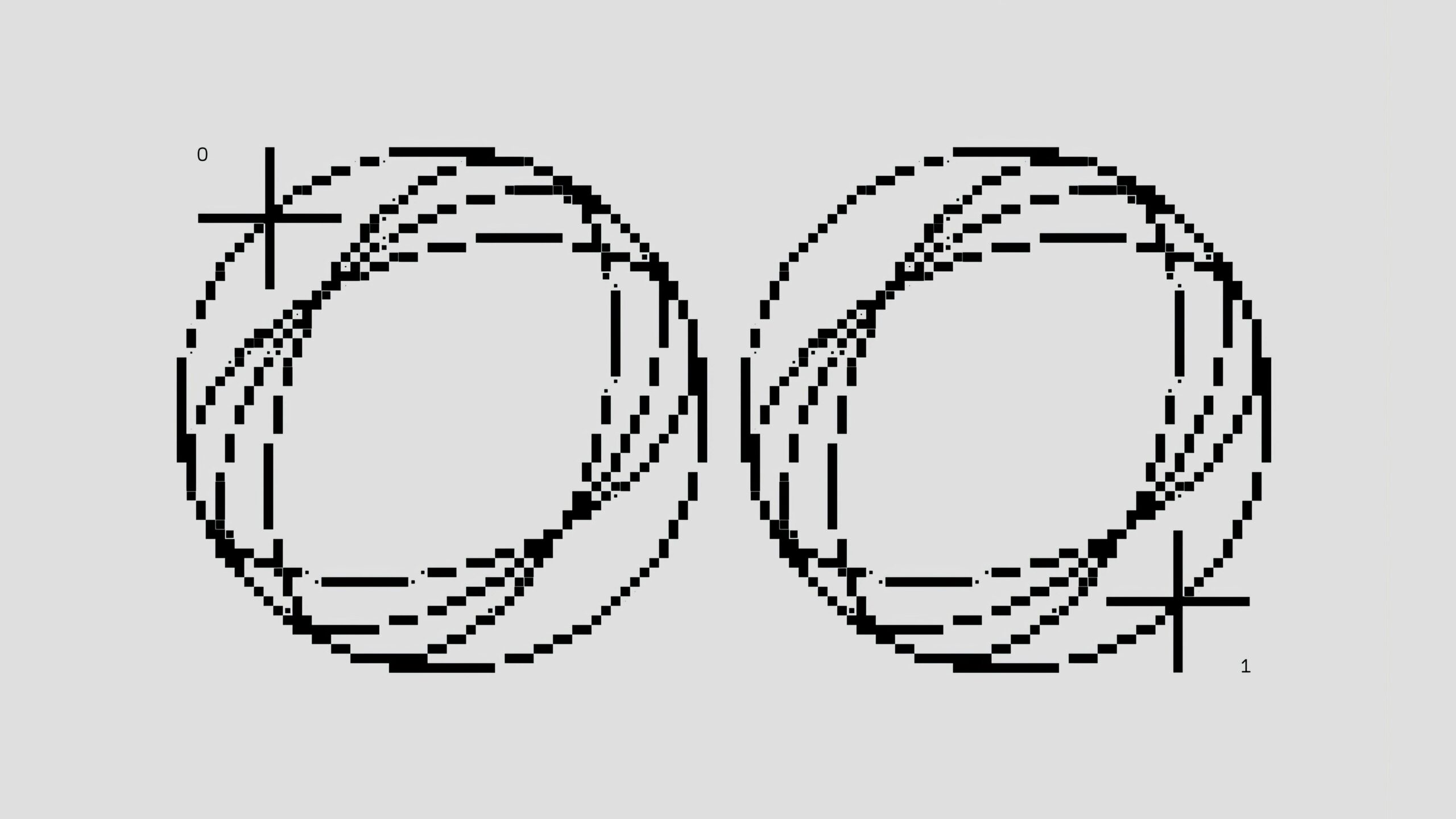

One of the most intriguing discoveries in prehistoric measurement came from the work of engineer Alexander Thom in the 1960s. After surveying hundreds of stone circles and megalithic monuments across Britain and France, Thom proposed the existence of a standardized unit he called the “megalithic yard,” measuring approximately 2.72 feet.

Thom’s research suggested that Neolithic builders used this consistent measurement across vast geographical areas and time periods, from around 3000 to 1500 BCE. If accurate, this would indicate a level of cultural coordination and mathematical sophistication previously unattributed to prehistoric societies.

However, Thom’s megalithic yard remains controversial. Critics argue that statistical analysis of irregular stone structures naturally produces apparent patterns. Supporters counter that the precision observed at sites like Stonehenge and the Ring of Brodgar cannot be coincidental.

Recent archaeological techniques, including 3D laser scanning and advanced statistical modeling, have reopened this debate. Some studies support the existence of standardized measurements in megalithic construction, while others suggest regional variations were more significant than Thom acknowledged.

⚖️ Weight and Volume in Ancient Trade

Measuring weight and volume presented different challenges than measuring length. Archaeological excavations have uncovered remarkably uniform sets of stone weights from ancient Indus Valley sites dating to 2500 BCE. These weights followed a binary system, with each unit doubling the previous one, demonstrating mathematical thinking far ahead of its time.

The Indus Valley civilization used cubic weights based on a unit of approximately 28 grams. Archaeologists have found these weights in archaeological sites separated by hundreds of miles, indicating extensive trade networks and standardization across the civilization.

In Mesopotamia, barley grains served as an early standard for small weights. The shekel, one of the oldest weight units, was originally defined as the weight of approximately 180 barley grains. This grain-based system eventually evolved into more standardized metal weights as trade became more complex.

🌾 Agricultural Measures and Land Division

The development of agriculture created immediate needs for measuring area and volume. Ancient societies needed to calculate field sizes, estimate harvest yields, and divide land among community members. These practical requirements led to some of the earliest sophisticated mathematical thinking.

In ancient Egypt, the “aroura” measured approximately 2,756 square meters and served as the basic unit for land taxation. Egyptian surveyors, known as “rope stretchers,” used knotted ropes to measure field boundaries after the annual Nile floods. This system required understanding basic geometry and proportional relationships.

The Babylonians developed an even more advanced system based on the “iku,” approximately 3,600 square meters. Their sexagesimal (base-60) number system, which we still use for measuring time and angles, emerged partly from agricultural measurement needs. This mathematical innovation enabled more precise calculations for irrigation systems and crop planning.

🏗️ Architectural Precision Before Precision Tools

The architectural achievements of prehistoric and ancient civilizations reveal sophisticated understanding of measurement, proportion, and scale. The Great Pyramid of Giza, constructed around 2580 BCE, demonstrates measurement accuracy that seems impossible without modern instruments.

The pyramid’s base forms a nearly perfect square, with sides varying by less than 2 inches over a length of 756 feet. The four sides align with the cardinal directions within a fraction of a degree. This precision required not just standardized measurement units but also advanced surveying techniques and mathematical knowledge.

Similar precision appears in other ancient structures worldwide. The prehistoric temple complex of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey, dating to 9600 BCE, features massive T-shaped pillars arranged in circular patterns with apparent geometric relationships. Mayan pyramids incorporate sophisticated astronomical alignments and proportional relationships based on their measurement systems.

🌍 Cultural Exchange and Measurement Standardization

As trade networks expanded, the need for compatible measurement systems became critical. Archaeological evidence suggests ancient civilizations didn’t develop their measurement systems in isolation. Maritime trade in the Mediterranean, overland routes connecting Asia and Europe, and trading networks in the Americas all facilitated the exchange of measurement ideas.

The spread of certain measurement units across vast distances supports this theory. The foot, for instance, appears with remarkable consistency across cultures that had contact through trade. While variations existed, the general concept and approximate size remained relatively stable from ancient Greece to Rome to medieval Europe.

Conversion systems also emerged as different cultures interacted. Merchants needed to translate between local and foreign measurement systems, leading to the development of early conversion tables. Some of these tables, preserved on clay tablets from ancient Mesopotamia, demonstrate sophisticated mathematical understanding of proportional relationships.

🔬 Modern Methods for Ancient Mysteries

Contemporary archaeology employs increasingly sophisticated tools to investigate prehistoric measurement systems. Ground-penetrating radar reveals subsurface structures without excavation, allowing researchers to analyze architectural patterns across entire settlements. Laser scanning creates precise 3D models of ancient monuments, enabling statistical analysis of measurement patterns.

Isotope analysis of materials helps trace trade routes and cultural connections, providing context for understanding how measurement standards spread. Computer modeling allows researchers to test theories about ancient construction techniques and the measurement systems they required.

These modern methods have revealed surprising sophistication in prehistoric measurement. Recent analysis of ancient Egyptian construction sites found evidence of standardized modular units used in planning, suggesting architects worked from scaled drawings or models—a level of planning previously thought impossible without modern drafting tools.

📐 Mathematics Hidden in Ancient Design

Many ancient structures incorporate mathematical relationships that suggest intentional design rather than accident. The golden ratio (approximately 1.618), revered for its aesthetic properties, appears in structures predating formal mathematical description of this proportion.

The Parthenon in Athens, though not prehistoric, exemplifies principles likely used by earlier builders. Its dimensions incorporate multiple mathematical relationships: the ratio of column height to diameter, the relationship between width and length, and the subtle curvature of supposedly straight lines. These proportions required sophisticated measurement capabilities.

Prehistoric monuments also show geometric sophistication. Stone circles often incorporate integer ratios in their dimensions. Some researchers argue these patterns reflect proto-mathematical knowledge passed down through generations before written mathematics emerged.

🌟 Astronomical Alignments and Measurement

Many prehistoric structures align with astronomical events—solstices, equinoxes, or specific star risings. Creating these alignments required precise angular measurement and long-term observation. The measurement systems used for construction had to accommodate both terrestrial and celestial dimensions.

Stonehenge’s alignment with the summer solstice sunrise demonstrates prehistoric understanding of both spatial measurement and temporal cycles. Creating this alignment required measuring angles with precision comparable to a compass, though magnetic compasses didn’t exist in Neolithic Britain.

Similar astronomical alignments appear worldwide: Newgrange in Ireland, Chaco Canyon in New Mexico, and Angkor Wat in Cambodia all demonstrate sophisticated measurement of both space and celestial cycles. These structures suggest measurement systems integrated multiple scales, from handbreadths to cosmic proportions.

🔍 Challenges in Interpreting Ancient Measurements

Reconstructing prehistoric measurement systems faces significant challenges. Erosion, structural damage, and incomplete archaeological records make precise analysis difficult. Additionally, we must guard against projecting modern assumptions onto ancient practices.

The concept of absolute precision itself may be anachronistic. Ancient builders might have prioritized different aspects of measurement than we do today. Proportional relationships might have mattered more than absolute dimensions. Ritual or symbolic meanings might have influenced apparent irregularities we interpret as imprecision.

Cultural context matters enormously. A measurement unit that seems arbitrary to modern observers might have held deep cultural significance for ancient users. Understanding why ancient people measured the way they did requires reconstructing not just their tools and techniques but their entire worldview.

💡 Lessons from Ancient Measurement Systems

Studying prehistoric measurement teaches us more than historical facts. It reveals how humans solve fundamental problems, adapt tools to needs, and standardize practices across communities. The development of measurement represents one of humanity’s first technological standardizations—a prerequisite for complex civilization.

Ancient measurement systems also demonstrate impressive practical mathematics. People who left no written equations nonetheless understood proportions, scaling, and geometric relationships. This practical mathematical knowledge enabled architectural and engineering achievements that still impress today.

Furthermore, the persistence of certain measurement principles across millennia suggests some approaches to quantifying the world may be fundamentally human. Our continued use of body-based references in casual measurement (“about a foot long,” “a stone’s throw away”) echoes our prehistoric ancestors’ original solutions to measurement challenges.

🎯 The Legacy of Ancient Measurement Today

Traces of prehistoric measurement systems persist in modern standards. The foot, yard, and mile all descend from ancient units. Even the seemingly rational metric system wasn’t created in a vacuum—it built upon millennia of measurement evolution, simply choosing Earth’s dimensions rather than human bodies as its standard.

Understanding ancient measurement systems helps us appreciate how technology develops. Modern precision instruments didn’t appear suddenly; they represent countless incremental improvements over thousands of years. Each generation refined the tools and concepts inherited from predecessors.

As we develop new measurement technologies—laser rangefinders, GPS positioning, atomic clocks—we continue a tradition beginning with our ancestors stretching ropes between markers or counting steps across fields. The fundamental human impulse to measure, quantify, and understand our world remains unchanged, even as our tools grow ever more sophisticated.

The mysteries of prehistoric measurement remind us that ancient peoples possessed remarkable intelligence, creativity, and mathematical insight. Their solutions to measurement challenges, developed without modern tools or formal scientific methods, laid foundations for all subsequent technological development. By uncovering these ancient systems, we connect with our collective human heritage and gain deeper appreciation for the ingenuity that has always characterized our species. 🌟

Toni Santos is a sacred-geometry researcher and universal-pattern writer exploring how ancient mathematical codes, fractal systems and the geometry of nature shape our sense of space, form and meaning. Through his work on architecture of harmony, symbolic geometry and design intelligence, Toni examines how patterns—of land, building, cosmos and mind—reflect deeper truths of being and awareness. Passionate about math-mystics, design-practitioners and nature-thinkers, Toni focuses on how geometry, proportion and resonance can restore coherence, meaning and beauty to our built and living environments. His work highlights the convergence of form, perception and significance—guiding readers toward a geometry of life-affirming presence. Blending architecture, mathematics and philosophy, Toni writes about the metaphysics of pattern—helping readers understand how the structure of reality is not only observed but inhabited, designed and realised. His work is a tribute to: The timeless wisdom encoded in geometry, proportion and design The interplay of architecture, nature and universal pattern in human experience The vision of a world where design reflects harmony, resonance and meaning Whether you are a designer, mathematician or curious explorer, Toni Santos invites you to redirect your gaze to the geometry of the cosmos—one pattern, one space, one insight at a time.